This insight should take around 8 minutes to read.

Earlier this month Nexus Polytech made a submission to a consultation paper published by the NSW Government about improving rental laws in New South Wales. One of the primary areas the Government was seeking feedback on was strengthening of privacy and data protection laws for citizens, particularly for tenants.

In Australia, the primary legislation governing data privacy is the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), which defines the Australian Privacy Principles (APP), a framework for privacy and data protection and imposes compliance obligations and penalties on certain entities covered by the Act (APP entities).

The 13 APPs range from how APP entities must collect and store information, to how they must deal with collected information, and requirements for transparency of process and access to data.

As information technology evolved and became a more significant part of daily life, so did the threats and attacks that bad actors could perpetrate. Accordingly, the Privacy Act was regularly updated over the decades to respond to the ever-changing nature of the data landscape.

For instance, when it was first introduced, the Privacy Act only covered certain government agencies. This was changed in 2000 when the Privacy Act was amended to regulate the private sector with the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000.

The three million dollar line

The 2000 amendments introduced Section 6D of the Act, the small business exemption, which remains in the Privacy Act, virtually unchanged 22 years after it was introduced. The section exempts small businesses and organisations from certain obligations imposed by the Privacy Act if their annual turnover for the previous financial year is $3,000,000 or less and if they obtain the consent of individuals to collect and/or disclose their personal information.

At the time of the amendment, the Attorney General who introduced the Bill stated in his second reading speech:

While protecting privacy is an important goal, it must be balanced against the need to avoid unnecessary costs on small business. For this reason, only small businesses that pose a high risk to privacy will be required to comply with the legislation.

The Attorney General during his Second Reading Speech

This $3,000,000 threshold has remained unchanged since it was introduced in 2000.

The rationale behind the small business and small organisation threshold was that it was a costly and resource-intensive endeavour to comply with the obligations of the Act and that small businesses did not have the type and/or volume data valuable enough to make them a target for attackers.

While this may have been the case for most small businesses in 2000, it would be difficult to successfully argue this point in 2023.

In 2017 the Privacy Act was amended again with the Privacy Amendment (Notifiable Data Breaches) Bill 2016, which introduced mandatory data breach notification provisions for agencies, organisations and certain other entities that the Act regulates.

In the second reading of the Bill in the Australian Senate, a Senator made the point:

The threshold determining who this bill applies to should not have anything to do with turnover. It should have regard to how much material those entities are holding. Really, their turnover is irrelevant. There are companies and entities such as researchers operating under much smaller turnovers than that who are still amassing large amounts of private information.

Australian Senate debating the Privacy Amendment (Notifiable Data Breaches) Bill 2016

More turnover does not always mean more data

While the general correlation between the turnover of a business or organisation and the volume of data it holds may have been suitable in an age where the amount of digitised data was a fraction of what it was today and cyber attacks were fewer, evolution in technology necessitate a more robust approach that considers the volume and sensitivity of data.

There are circumstances where businesses in the same industry can have different volumes of data stored yet have different obligations under the Privacy Act due to the impact of economic factors on their annual turnover.

In our submission to the NSW Government, we made the point using the following hypothetical example based on real-world data.

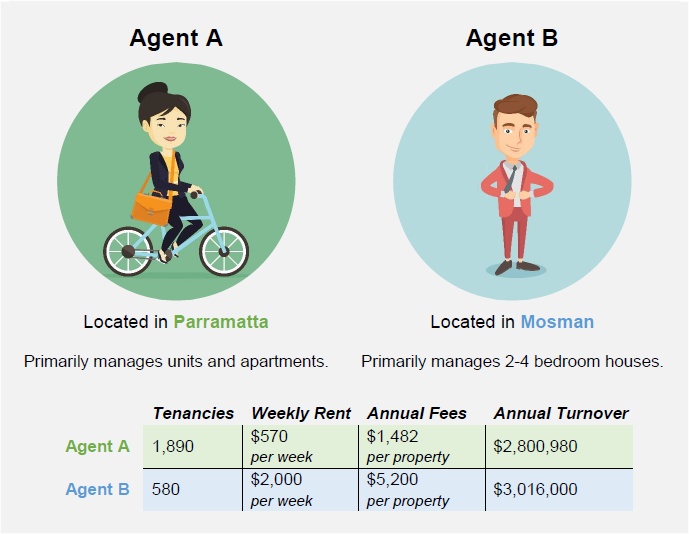

Say we have two real estate agencies located in different parts of Sydney who both charge their landlords exactly 5% in management fees (including taxes and all sundries). Agent A is situated in the suburb of Parramatta and primarily manages units and apartments. In contrast, Agent B is situated in the suburb of Mosman and primarily manages two to four-bedroom houses.

Based on the median weekly rent (according to data from REA Group) for properties in their respective suburbs, Agent A, with 1,890 tenancies, has an annual turnover of $2,800,980. In contrast, Agent B, with 580 tenancies, has an annual turnover of $3,016,000.

Despite Agent A having more than three times as much information as Agent B and thus being more at risk of a cyber attack that could impact more people, Agent A is under the threshold and meets the small business exemption in the Privacy Act, whereas Agent B is not.

This example demonstrates that using annual turnover as the sole metric to determine the amount of potentially at-risk data could lead to fewer protections where needed and a false sense of security.

Changing attitudes towards the small business exemption

A series of high-profile and severe data breaches in the last few years have accelerated discussions about strengthening data protection and privacy laws.

In October 2020, the Australian Attorney-General’s Department released an issues paper to review whether the scope of the Privacy Act and its enforcement mechanisms remain fit for purpose, and sought submissions from industry and relevant stakeholders. One of the matters explored by the paper was the small business exemption.

The subsequent discussion paper noted a high level of interest in the small business exemption from submissions received, with many submissions supporting removing the exemption or adjusting the threshold.

In contrast, submissions made by representatives for small business noted that small businesses will have reduced competitiveness relative to larger businesses if the exemption were removed due to the burden of new compliance costs.

The issues paper and discussion paper led to the release of the Privacy Act Review Report 2022, which proposed reforms to strengthen the protection of personal information and the control individuals have over their information.

Proposal 6.1 of the report proposed to remove the small business exemption, but only after an impact analysis, consultation, development of appropriate support, and small businesses are in a position to comply with the new obligations.

Alternative proposals from industry have suggested adjusting the threshold to strike a more appropriate balance between data protection and business/organisation compliance.

In addition to reform at a Federal level, several State Governments are implementing legislation and regulation to strengthen data protection across their States and among specific industries. There will likely be changes to the small business/organisation exemption in the Privacy Act over the next few years. What shape these reforms will take remains yet to be seen.

One thing is for sure, the use of annual turnover to determine the privacy and data protection obligations for a business or organisation is likely to be succeeded by more robust approaches to privacy that strengthen data protection for users and place greater obligations on small businesses and organisations.